The Gen Z take on film history

There’s a lot to be said for Steven Spielberg. Most of what’s said also seems to be overwhelmingly positive, for one of the greatest storytellers of our time.

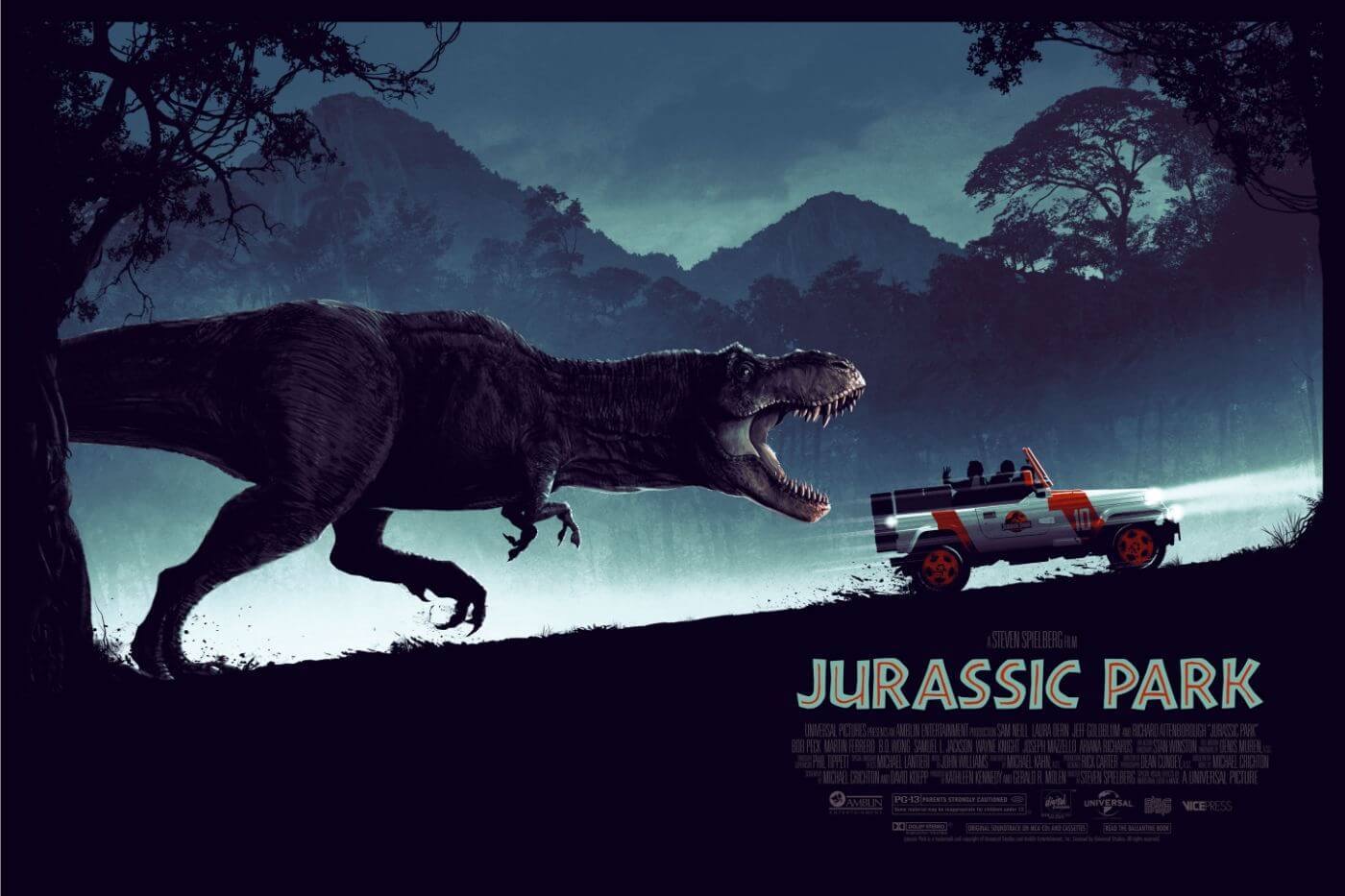

It fills me with regret that I was born too late to have witnessed the reception to Jurassic Park. It also fills the Gen-Z mind that has never known a world without CGI that a film like this is so capable of spectacle at scale, a spectacle that, 30 years later, still holds up.

The first lesson to take from this is that good filmmaking will supersede its time, and often in unexpected ways (think to the latent homoeroticism of Top Gun). Competent and colourful acting will, as well, persevere beyond the prison of the moment of performance. Consider Jeff Goldblum, as seen in Jurassic Park. A character who has no real purpose other than pure embellishment rises to legend. It can, and should, be said that the three inevitabilities remain- Death, Taxes, and the Quirky Sex Appeal of Jeff Goldblum. I and the 3 other inhabitants of this Monday evening showing let out audible gasps at the sight of his now-famous unbuttoned reclined form. When he flirts, he does it with his encyclopaedic wisdom and fervent charisma, ageing this performance like fine wine into the more aware 2020s, a rarity for such Casanova-esque characters.

This brings us to another lesson: No, the 2020s are not any more “woke” than the 80s or 90s. This film does not bring a cringe to the face, except at the sight of its ancient computers, and is brilliantly fair and egalitarian in its showing of a paleobotanist, who, by the way, happens to be a woman. This is a fact you’re reminded of only when she calls out Attenborough’s character David Hammond’s sexism by calling it just that: sexism. If cancel culture is something you hate, start with 1993’s Jurassic Park. She is not ‘one of the guys’ either, lest her femininity be condescended in that particular way, nor is she a femme fatale. She is a curious and passionate scientist, before all, with a secondary but clear desire to have children with her partner. What Spielberg and Michael Crichton, the original author, thus show is that if you want to write a film that isn’t sexist, a) You can, and b) it’s really not that much effort.

While Stephen Spielberg, by some accounts, may not get his flowers for his masterful use and understanding of the technologies at his disposal, Jurassic Park is not subtle. Nerdwriter1 has a lovely breakdown of the brilliance involved in Spielberg and Ben Burtt’s auditory storytelling in 2005’s Munich.

This is not an avenue that Spielberg left untrodden in Jurassic Park. There is a certain filmmaking boldness involved in the decision to have the T-Rex attack scene, a 10-minute sequence, be completely devoid of music and have the pink noise of rain and the echoes of the unseen Rex’s footsteps be the entire soundtrack. Bolder still, it must be said, to do that when you have John Williams of all people scoring your film.

.

Gary Rydstrom, while being allowed to shine sonically in this sequence, also had his work cut out for him. He was not Speilberg’s first port of call for this film, as he often isn’t; Spielberg prefers Ben Burtt, who happened to be busy. Rydstrom came fresh off an Oscar for Terminator 2’s futuristic soundscapes and was instantly asked to imagine the prehistoric. Academics gave him no guidance, and he just decided to make the best film he could. Having recorded a whole menagerie of animals, Rydstrom took the approach of layering multiple to make the ethereal dinosaurs’ calls. Of particular pride to him, and a story he tells often, is the T-Rex, which, amongst other things, is mainly the shriek of a baby elephant.

You don’t watch a movie with your ears, though. Visually, Spielberg delivers his usual brilliance with an edge of innovation. The film nerd fun fact here is the aspect ratio: 1.85:1, which is taller than films were at the time. Why? Because dinosaurs are taller than they are broad, and that little bit of extra vertical spacer makes for the otherworldly sense of scale we experience. Interesting also are his choices in showing the dinosaurs, or, more appropriately, not showing them. You won’t notice it, because, well, he’s that’s good, but you don’t really see a full dinosaur in frame through a film.

You see a limb here, a head and a neck elsewhere, and the torso downward for a large part of the T-rex’s screentime. This is a film of fakeouts and reveals, and the selectively scarce viewings of the dinosaur are evocative and suspenseful. Before we even see a hint of a dinosaur, we see people being affected by them: An employee is killed in the starting scene, you see the goat the T-rex kills a quarter of an hour before you see the actual creature, and the camera lingers on our glamorous lead characters’ reactions to their first dinosaur sighting for a gratuitously long while before begrudgingly showing us the dinosaurs from a distance.

None of these observations are unique or original, because Jurassic Park, like many of Spielberg’s films, has been studied and analysed to death. A lot of which was done well before I was born at the turn of the millennium. The recordings of felled redwood trees that form the sonic basis for the T-rex’s footsteps in the film are an appropriate metaphor for Jurassic Park. The tree fell in the forest, and it was heard and heard and heard again.

In this year that Jurassic Park turns 30, Ben Hur turns 64 and Casablanca turns 81. Top Gun: Maverick, Barbie and Oppenheimer, have brought a second golden age of cinema, but being able to record stories is what makes them timeless. Jurassic Park is still a story told outside a time capsule, and in an age of Elon Musks and Jordan Petersons, consuming warm and earnest fiction is more necessary than ever. Consuming culture is necessary for the advancement of a species.

Robert Oppenheimer might’ve been one of the best-read public figures in the history of geopolitics. He read fiction and history. Do both, go watch something like Jurassic Park.

Leave a Reply